Welcome to the first post of 2010!!

I just got back from Seattle one week ago from the annual meeting for the Society of Integrative and Comparative Biology, or SICB in short. So here is a short report about some of the inspirations I received over the course of the 10 days Seattle visit. For the limited space, I will only mention three topics with: 1) ideas that resonates with my current research; 2) something about

Manduca sexta; 3) the most entertaining contents.

To start with, I would like to acknowledge those researchers working on plant biomechanics. After staring at the quasi-static locomotion of caterpillars for 4 years, I can really appreciate the intricate movements without dynamics as also in plants. Really, caterpillar crawling is a "static problem" only that people don't like to hear about "static locomotion" so "quasi-" makes it sound better. Of course, plants movements are all driven hydraulically, but cellulose fibers can define the deformation. The morphology very much depends on the material properties and internal pressure. For climbing plants, stem development and attachment scheme are highly correlated. Those that attach to host substrate tightly can be soft, while the ones that hang on to forest tapestry loosely would need stiffer stems to self support. This principle of substrate interaction really resonates with the "environmental skeleton" hypothesis I proposed. For a big fat caterpillar with many prolegs attached to the substrate, no internal structural support is needed. In fact, compliance is imperative to allow conforming to the substrate, just like those tightly attached plants.

This year's SICB also had a lot of animal flight stuffs. In particular,

Manduca hawkmoth flight has been a highlight. Thanks to the modern high-speed videography and kinematics tracking software, wing strokes can be digitized at many thousands of frames per second rate. Much attention has been delegated to turning maneuvers, especially in the yaw direction. In general, hawkmoth and other big insects create asymmetric effective wing angle of attack to turn. This change of stroke plane can generate a fairly acute turn, and we can find this strategy in many current radio controlled micro-ornithopters. After watching so many slow-motion of moth flying, it occurred to me that body weight shift must play a key role for stability as well. While most micro-ornithopters don't use tail for turning anymore, they still need it to smooth out the unsteady air flow from the wing. To create a tail-less flapping flight robot, we might want to model the body coordination as well. For any flapping flight agent on the order of a few grams, it seems to me that weight shift is as effective (if not faster) for stability compensation as wing stroke modification.

Finally for the topic with the most entertaining contents, I would like to mention some work on maximum performance of musculoskeletal systems. Although I am currently working with a critter without any skeleton, my original biology training was functional morphology of skeletal systems. In plain English, that means I held scalpels more often than pipettes. I was the student helper at this session called "Terrestrial Locomotion -- Jumping" with the session chair Steve Reilly. It's a strange feeling to see Dr. Reilly because I once read a lot of his work and almost did my undergraduate thesis on frog jumping. Anyways, the first talk of this session was probably the most entertaining talk I went to in SICB 2010. It was about why jumping frogs contests produced much better jump distance record than the scientific research. Well, apparently it's all in the arts of these professional "frog jockeys", which are unfortunately kept secret. However, the investigators in this research did find out one well-tuned factor that affects maximum muscle performance: temperature. This is probably a general issue for all poikilotherms (animals don't actively maintain a constant body temperature) which can be easily affected by climate change. In any case, although it's ambiguous what these "frog jockeys" were doing to their frogs, it was absolutely hilarious to see them "jump their frogs" with the utmost seriousness.

Of course, there was a lot more impressive research presented in this meeting. I was simply overwhelmed by Wednesday afternoon that I had to stop going to the talks in order to recall my own presentation scheduled on Thursday morning. It's good to be at a conference like this and feel connected to this fun community of scientists.

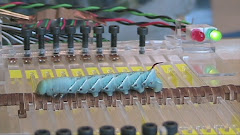

Taking the inspiration, they also created a tail-less micro-ornithopter with all the control electronics and sensors on-board. (very impressive works!!)

Taking the inspiration, they also created a tail-less micro-ornithopter with all the control electronics and sensors on-board. (very impressive works!!)

.jpg)